EU Unveils Defense Readiness Roadmap to Enhance Security by 2030

The European Commission has launched its Defense Readiness Roadmap, aiming to bolster the EU's military capabilities by 2030 in response to evolving threats, particularly from Russia. The roadmap includes four flagship projects to enhance collective security.

Key facts

- The roadmap aims for the EU to respond to threats by 2030.

- Key projects include the European Drone Defense Initiative and European Air Shield.

- The initiative is driven by requests from frontline member states.

- Germany will lead the European Air Shield project.

- The European Defence Agency will support project coordination.

5 minute read

The European Union has set itself an ambitious goal: to be ready for any military contingency by 2030. In its new White Paper on European Defence Readiness, released in March 2025, Brussels lays out the most comprehensive roadmap yet to build a stronger, more self-sufficient European defence system. The paper arrives amid worsening global instability, persistent Russian aggression, and growing concern that Europe remains too dependent on external powers—chiefly the United States—for its security.

At the heart of the plan is a recognition that Europe’s defence industrial base is fragmented, slow, and under-resourced. The Commission and the European External Action Service argue that this patchwork approach must end. The White Paper calls for Europe to act as one defence ecosystem—coordinating procurement, pooling demand, and creating scale for its industry. The aim is to close critical capability gaps and build a continent-wide market capable of producing arms, ammunition, and technology “at the speed and volume required by today’s threats.”

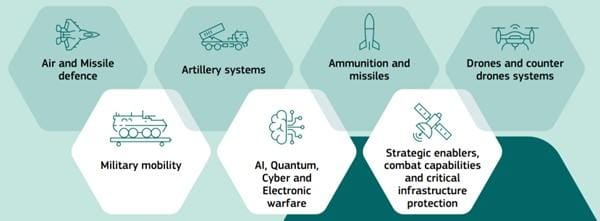

The document highlights seven priority areas where collective action is most urgent: air and missile defence, artillery, ammunition, drones and counter-drone systems, military mobility, advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence and quantum computing, and a range of strategic enablers including refuelling, airlift, and maritime surveillance. Each represents a domain where European militaries have either under-invested or remain dependent on non-EU suppliers.

Brussels also intends to overhaul the logistical foundations of European security. Military mobility—moving troops and equipment rapidly across the continent—has become a central concern, especially in light of the war in Ukraine. The White Paper pledges to remove administrative bottlenecks and invest heavily in dual-use infrastructure such as bridges, railways, and ports. By the end of 2025, the EU expects to table new legislation on this front and designate four strategic corridors to speed up deployments.

Support for Ukraine is woven throughout the plan. The EU promises to sustain military aid, expand production of ammunition and air defence systems, and open its own defence market to Ukrainian participation. A joint EU-Ukraine task force will help integrate Ukrainian defence firms into Europe’s technological base, signalling that Kyiv’s future lies firmly within the European security framework.

Behind these strategic ambitions lies a financial architecture unlike anything the EU has attempted in defence policy. The ReArm Europe Plan—a companion to the White Paper—envisions up to 800 billion euros in additional defence spending over the coming years. Much of this would be unlocked through a new fiscal clause allowing Member States to exceed deficit limits for security investment, potentially releasing 650 billion euros. A further 150 billion could be channelled through a new EU instrument called SAFE, designed to offer loans for rapid rearmament and industrial scaling. The European Investment Bank and private investors are also expected to play a role.

The White Paper’s timeline is compressed and politically demanding. By mid-2025, the Commission plans to propose an “Omnibus Simplification” law to harmonise procurement rules across Member States, followed by a Defence Readiness Roadmap to track progress towards 2030. Other milestones include a technological roadmap for European armaments, new stockpile systems, and an observatory to monitor critical raw-material dependencies.

Yet even the Commission admits that implementation will not be easy. National interests remain deeply entrenched, and defence spending levels vary widely. Many of the most advanced military technologies—particularly in AI, quantum, and missile defence—will take years of research and testing before becoming operational. The goal of a truly single market for defence may also run into sovereignty concerns, export controls, and industrial competition.

Still, the White Paper marks a decisive shift in tone. After decades of under-investment, the EU is signalling that strategic autonomy requires hard power as well as diplomacy. The message is clear: Europe can no longer rely indefinitely on others for its security. Whether this ambitious plan becomes reality will depend on Member States’ willingness to turn words into budgets—and budgets into factories. But if even part of the roadmap is realised, 2030 could mark the first time the European Union possesses not only the will but also the means to defend itself.