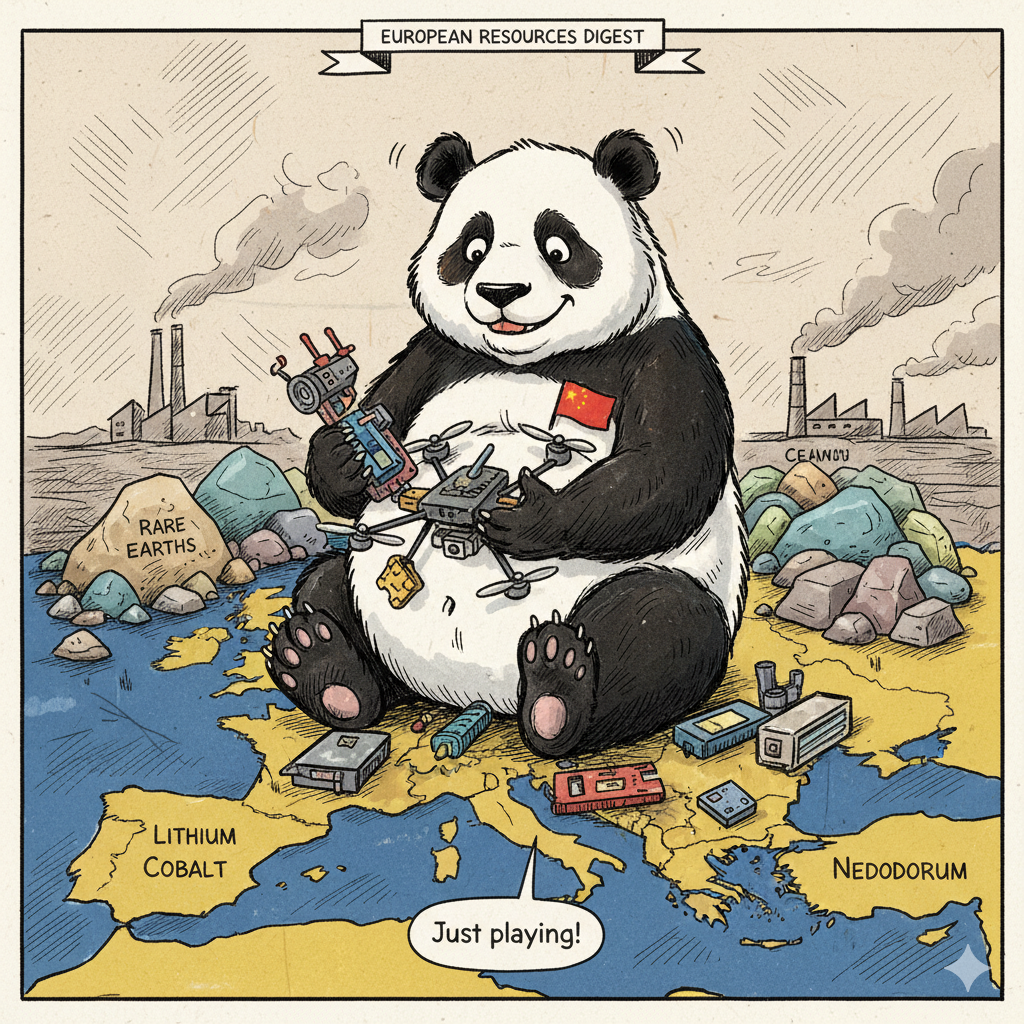

Europe’s drone heart still beats in China

While European drone startups multiply, their strategic foundation remains fragile. True sovereignty lies not in final assembly, but in the upstream production of critical components: magnets for motors, processed graphite for batteries, and low-cost sensors.

Key Facts

- Since 2018, EU import exposure sits above 30% for the machinery group that includes motors, batteries and chips, with China as top partner in 2024. (European Commission)

- DJI controls roughly 70% of global consumer drones in 2024, with European shares often higher though precise EU figures are scarce. (Global Market Insights Inc.)

- Mini-drone imports into the Netherlands were 94% Chinese in 2022. (OEC)

- Beijing imposed export controls on gallium and germanium in Aug 2023, on graphite from Oct 2023, and widened drone-related curbs in Oct 2025. (Herbert Smith Freehills)

- EU targets for 2030, 10% extraction, 40% processing, 25% recycling under the Critical Raw Materials Act, still leave big magnet and graphite gaps. (CRMA)

8-minute read

Europe is minting drone startups at a dizzying pace, yet the heart of many airframes still beats in Shenzhen. Motors built around magnets that Europe scarcely refines, flight controllers assembled on imported chips, gimbals and low-cost sensors sourced at scale from Chinese vendors, all turn a manufacturing boom into a strategic bottleneck.

Budgets are rising and programmes multiply, from drone walls to EU readiness goals for 2030. Autonomy isn't the same as spending. Unless Europe can secure magnets, cells, controllers and sensors, it will build drones but not truly control the supply chain. If China’s policy turns less friendly, companies will be left hanging.

Consumer and enterprise markets tell the same story. DJI commands the global consumer segment, roughly seven in ten units by most estimates, and European shares are often higher in practice given retail availability and price. In public safety and inspection, Chinese stacks still dominate the value end of the market, even as European integrators gain ground in specialised niches.

The upstream picture explains why. Brushless motors rely on neodymium-iron-boron magnets, often doped with dysprosium and terbium to handle heat. China dominates both processing and magnet production. Batteries lean on graphite anodes mostly refined in China, and while Europe has capable pack integrators, cell supply is still imported. Cameras and electro-optical payloads at the low and mid end of the market remain heavily Chinese because they are cheap, good enough, and delivered in weeks rather than months. Add radios, datalinks and commodity microcontrollers, and a typical European quadcopter quickly reads like a tour of Asian supply chains.

Europe isn't empty-handed. Credible vendors exist across the stack: motors and ESCs from Germany and the Czech Republic; Global Navigation Satellite Systems and inertial units from Switzerland, Belgium, Norway and France; rugged ground stations and secure waveforms from European teams; high-quality battery pack integration in France and Germany. The constraint is scale and cost. European motors and sensors are excellent but pricey with longer lead times; cells still come from Asia. Substitutes exist, just not yet at the volumes that attritable fleets demand, a gap laid bare by Ukraine.

The Critical Raw Materials Act sets 2030 targets that are necessary but perhaps not sufficient. Europe wants more extraction, more processing and more recycling within the single market. Even if those targets are met, magnets and graphite will remain tight for years. Meanwhile, Beijing’s export measures on gallium, germanium and graphite have introduced new licensing friction across electronics and battery inputs. Drone-specific controls have also been tightened, particularly on long-range communications and higher-end payloads. None of this stops trade, it simply raises the cost of delay.

In Brussels the language has hardened. On 25 Oct 2025 in Berlin, Ursula von der Leyen warned: “If you consider that over 90% of our consumption of rare earth magnets comes from imports from China, you see the risks here for Europe and its most strategic industrial sectors.” Two days later, after meeting China’s premier on 27 Oct 2025, European Council President António Costa said: “I shared my strong concern about China’s expanding export controls on critical raw materials and related goods and technologies. I urged him to restore as soon as possible fluid, reliable and predictable supply chains.”

Procurement adds another constraint. Governments across Europe want sovereign options for public safety and defence fleets. Some will ban Chinese subsystems outright for sensitive missions. That will push buyers toward European and allied vendors, as it should, but it will also raise prices in the short term and stretch delivery times while suppliers scale. The right response is not to back away from risk reduction, it is to pool demand so that vendors can invest with confidence. Europe did this for ammunition. It needs a drone-and-components version that covers magnets, anodes and controller boards, not just final airframes.

Company behaviour is already shifting. European brands selling into government markets emphasise transparent bills of materials. Integrators built on open flight stacks are mixing European motors, European or allied sensors, and non-Chinese radios to win tenders. German manufacturers are expanding output of dual-use systems that sit between commercial and defence. The Auterion and PX4 ecosystems have lowered software barriers for newcomers, though the hardware remains the gating factor. At the other end of the spectrum, Ukraine’s demand for low-cost first-person-view drones has shown how dependent Europe remains on Chinese COTS (Commercial off the shelf) components when the priority is price and volume.

Three plausible shocks illustrate the stakes. First, tighter Chinese export licensing on magnet technology, graphite or drone-related communications would hit availability quickly. Motors, gimbals and radio modules would grow scarcer within months, with prices up sharply and delivery dates slipping across the board. Second, if European governments move faster to restrict Chinese subsystems in public fleets, there will be a near-term price bump and a scramble to qualify substitutes. That isn't a reason to delay, it is a reason to coordinate. Third, maritime disruption in the Red Sea or the Taiwan Strait would slow Asian electronics for weeks, perhaps longer. Safety stock would cushion the blow, but only for buyers who planned ahead.

The counterpoints matter. Dependency is already falling in the top tier of defence, where budgets can absorb premium components and schedules justify longer lead times. European firms can now field fully non-Chinese platforms and payloads that meet U.S. and allied security standards. Investment is flowing into magnet projects, graphite processing, battery lines and chip packaging across the continent. Some promises have slipped or shrunk, but the direction is right.

Take Bavaria’s Quantum-Systems Vector. In its government fit it swaps the usual bargain-bin stack for European sensors and radios, and both the Bundeswehr and Ukraine have flown it. It shows the dependency is not total. You can build credible systems without Chinese guts. The rub is cost and tempo. It flies well and buyers like the transparency, but it has not yet hit the price or replenishment speed that frontline units need when losses come every week.

The practical to-do list is short. Treat motors, ESCs, battery cells and sensors as defence-critical. Use readiness funding to de-risk upstream capacity with guaranteed off-take. Mandate dual sourcing in public tenders from 2026 and reward designs that can swap controllers, radios and sensors without a full redesign. Pre-position spares for nine to twelve months. Publish simple, standard bills of materials to drive commonality and scale. And keep a close eye on the Baltic and Nordic “drone wall”, where cost, quantity and resilience will decide whether Europe can build what it plans to defend.

Conclusion

Europe’s drone build-up will be judged by whether units can be fielded at scale, fast, and without calling Shenzhen for parts. The gap between assembly and autonomy is upstream patience: cells, magnets, chips and sensors produced or secured in Europe and allied markets. That is industrial policy, not branding.

Pool demand, mandate dual sourcing, and finance the dull pieces of the stack so costs fall and lead times shrink. By 2030, Europe can fly sovereign where it matters, with attritable systems replenished in weeks and premium payloads free of licensing surprises. Fail at the upstream work and the continent will keep paying more, waiting longer, and ceding leverage in every crisis.

Autonomy is a supply chain, not a slogan.

Originally published on DroneIntel.eu by José Vadio, Oct 2025