The Age of the Drone Swarm

The evolution of drone technology is leading to the emergence of swarming capabilities, which promise to transform military operations. This article explores the implications of swarming drones for future warfare, including strategic advantages and challenges in implementation.

Key Facts

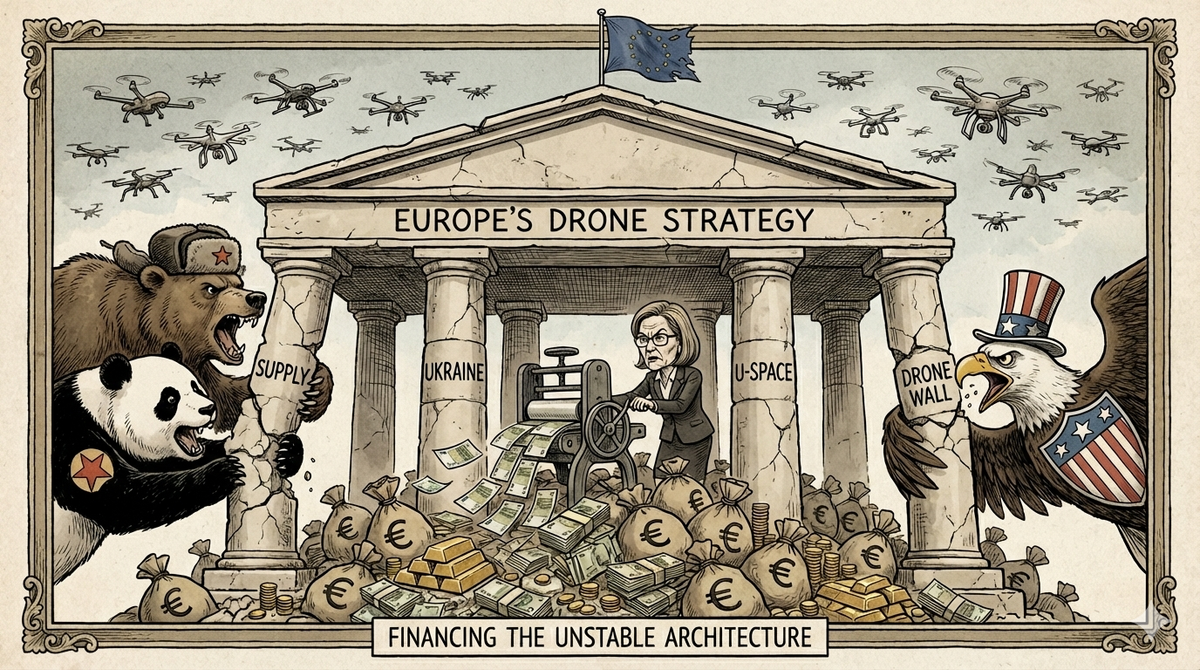

- The EU’s “drone wall” idea is edging toward a broader European Drone Defence Initiative, but it faces political and technical hurdles, including how to integrate with NATO systems and who pays. Reuters

- A UK–Latvia Drone Coalition has moved from slogans to orders, aiming to deliver tens of thousands of small drones to Ukraine and seed mass production in Europe. Drone Coalition

- China’s advances in swarming, from forest-navigating autonomous teams to record breaking light-show formations and survivability tricks like “terminal evasion,” raise the bar Europe must clear. The Verge

8 minutes read

On a grey November morning by the Tagus, a sharp wind blows in from the Atlantic, carrying the first real chill of autumn. Near the redeveloped warehouses and accelerators of eastern Lisbon, a small procession of quadcopters lifts off, their motors whining against the breeze. Tourists, collars turned up, barely look up. Engineers in hoodies pretend not to watch too closely. It is, to the casual eye, yet another European startup testing their newest gadgets that they hope one day will be part of the European Drone Wall. The Docklands drones might or might not decide Europe’s fate.

The picture is mundane and oddly momentous. Europe’s political class is fretting about budgets and treaties while the practical business of airpower is drifting a few metres above the water, battery by battery, update by update. The real argument is not whether drones matter. It is about who sets the rules and builds the capacity. Europe can still turn incremental strengths into strategic leverage. Do that and the continent becomes a standard setter for autonomy, a reliable co-producer with Ukraine, and a credible partner for allies that do not always agree with each other. Miss it and Europe imports not just airframes but habits, vulnerabilities, and timelines written elsewhere. “Drone diplomacy” sounds like branding. In practice, it is procurement plus law plus industrial policy that actually arrives on time.

A brief history helps. Years of under investment left European air defences threadbare and procurement cycles allergic to speed. The war in Ukraine forced improvisation at scale, with cheap FPV craft, payloads, and AI assisted targeting making a mockery of old cost curves. Brussels has responded with a Defence Readiness Roadmap 2030 and, inside it, a continent-wide counter-drone push that began life as a “drone wall.” It is gaining shape, although the politics are messy and the engineering demands are high, from spectrum discipline to sensor fusion and legal authority. Still, the direction is clear enough to warrant serious planning, funding, and standards work.

How to turn that into something that survives contact with reality? Four pillars. They hang together.

First, supply at scale. The point is not a trophy platform. It is volume, diversity, and a steady pipeline. The UK Latvia Drone Coalition is doing something refreshingly unEuropean: publishing quantities, placing orders, and talking in weeks rather than years. Procurement rounds are already moving, with commitments to deliver large batches of small drones to Ukraine and to channel money through an international fund. For a continent used to fractious tenders, the sight of a small Baltic state brokering mass production is instructive. Small states can move fast. Large ones can either learn or be passengers. If Brussels is sensible, it will braid this pipeline into EU instruments rather than set up a rival scheme that burns time proving a point.

Second, co-production with Ukraine. This is where Europe can be either serious or sentimental. Serious means assembly lines on Ukrainian soil, joint ventures that embed wartime feedback into European designs, and training loops that institutionalise what Ukrainian units have learned the hard way, such as emissions discipline, repair in hours, and trusting mission software. Sentimental means partnerships that never outlast the press conference. Ukrainian units have already moved from hand-flown teams to AI enabled multi drone groups that reduce manpower per mission and compress decision cycles. Europe needs Ukraine’s battlefield learning as much as Ukraine needs Europe’s money and logistics. Co-production is not charity. It is industrial self-respect.

Third, rules as an engine, not a brake. The EU’s civil frameworks are caricatured as paperwork. In drones, they are leverage. Common categories, transparent certification routes, and interoperable U-space services create a continental market for dual-use suppliers. The spillovers into defence are immediate. Detect and avoid, resilient communications, navigation in ugly GPS conditions, and traffic services that keep mixed airspace safe are dual-use by design. Europe’s quiet superpower is to turn technical norms into geopolitical language. That should continue, but with more speed and more openness, so smaller firms can plug into open architectures rather than wait for a prime contractor to return their call.

Fourth, counter UAS and critical infrastructure protection. The lower airspace will not police itself. Europe needs layered defence that starts with deconfliction and identification, then moves through sensors and electronic attack, and ends with short-range interceptors that do not bankrupt the defender. There is progress. The British Army’s radiofrequency directed-energy trials neutralised two swarms in a single engagement and immobilised more than 100 drones across test events. That is the kind of cost-exchange Europe needs to regain the initiative. Legal clarity in peacetime matters as much as kit. Who presses which button over a refinery in Hamburg, a port in Piraeus, or a power station in Poland is not a theoretical question. It is a governance test that should be answered before a weekend shift becomes a crisis.

You can bolt financing across all four pillars. Predictable demand, not one-off grants, will decide whether factories buy machines and hire technicians. Europe already knows how to socialise risk for infrastructure. It should treat drone production, batteries, and electronics as industrial infrastructure too. If the European Investment Bank can back a bridge, it can back a motor line. The political scaffolding is there in the Commission’s roadmap and in national industrial programmes. The missing piece is execution that matches the tempo on the battlefield and the speed of adversary innovation.

Now to the uncomfortable bit. China. European conversation often treats Chinese “drone shows”, neat formations that draw QR codes in night skies, as spectacle. They are more than that. The same timing, positioning and distributed control that renders tidy holiday videos is a stepping stone to mass teaming. Chinese firms have repeatedly broken records, culminating in shows that reportedly passed ten thousand simultaneous craft. That is choreography at a scale Europe has not matched, and while a light show is not a strike package, the underlying system integration is a capability in its own right.

Beyond showmanship, Chinese labs and defence institutes are pushing survivability and autonomy. A widely reported “terminal evasion” concept adds side mounted rocket micro-boosters to small drones, enabling abrupt changes of course in the final seconds before interceptor impact. Simulations claim sharply higher survival rates. If fielded, such tactics would stretch European interceptors and complicate fire-control algorithms. This is not a reason for panic, but it is a nudge to accelerate Europe’s own spiral development.

Chinese research has also demonstrated autonomous swarms that navigate dense forests, coordinating without GPS or constant human control. Combine that with mass-manufactured small airframes and you get a playbook that emphasises scale, redundancy, and cheap attrition. Europe can answer this, but it will not do so by debating definitions. It will do so by shortening upgrade cycles, embracing open mission software, and funding test ranges where electronic warfare, autonomy, and counter-measures can tangle at real scale.

Europe is not standing still. The Commission’s defence roadmap points to a drone defence architecture that is meant to be substantially operational by 2026 to 2027, and several member states are building out their own layers. The trick is alignment. If the EU’s initiative conflicts with NATO integration or duplicates national efforts, it will underperform. If it leverages the UK Latvia pipeline, folds Ukrainian co-production into single-market scale, and anchors counter-UAS procurement in common standards, it might just move at a useful pace.

Lisbon offers a parable. Portugal talks often about nurturing unicorns, and its start-up policy has real momentum. If that civic muscle is pointed at unmanned systems, training technicians, backing component lines, and integrating small firms into European standards, it can help Europe build the “smart and affordable mass” everyone now claims to want. Drones are not magic. They are logistics plus code, wrapped in a political decision to buy enough of them.

Meanwhile, the battlefield keeps writing the syllabus. Ukraine has introduced AI-assisted swarming in live operations, albeit in small teams so far. That compresses decision timelines, frees operators, and exposes the defender to simultaneous problems. It is not science fiction. It is a warning that cost curves are moving in the attacker’s favour unless defence adapts. Europe will need both smarter soft kill and cheaper hard kill options, and a legal framework that lets trained people use them without paralysis.

There is one final housekeeping job: linking strategies to real industrial calendars. Announcing a “drone wall” wins headlines. Scheduling battery lines, RF components, airframes, and repair depots wins wars. The Coalition led by Latvia and the UK is the seed of a habit Europe needs to cultivate: publish the numbers, place the orders, keep score in public. If Brussels wants the wall, it should adopt that habit, not smother it with duplicate committees. And because this is Europe, all of that should be embedded in a standards stack that allows a Lithuanian camera module to talk to a Portuguese autopilot without drama.

Conclusion

Those drones over the Tagus are more than a pretty picture. They are a test of whether Europe can align politics, factories, and software fast enough to matter. The task now is to finish the standards, fund the production, and share the playbook. If Europe braids the Coalition’s volume with the EU’s roadmap, partners with Ukraine in the factory, and treats counter-UAS as a common utility, it can turn procedure into power.

China’s scale and survivability tricks are a spur, not an excuse. The risk is not that Europe lacks ideas. It is that it confuses announcements with outcomes. The Docklands drones might or might not decide Europe’s fate. More likely, the factories behind them will. And if Europe will not build those, someone else will write the rules over Europe’s infrastructure and sell them back to us as inevitability.

Originally published on DroneIntel.eu by José Vadio, Nov 2025